Family Ties and Informal Learning

Grandparent-Grandchild Relationships

One of my earliest memories is sitting on my grandmother’s living room floor, surrounded by stacks of National Geographic magazines. Their yellow spines peeked out from under her coffee table, beckoning me to explore the natural wonders within their glossy pages. On the table’s surface, piles of Discover and Scientific American magazines left just enough space for her ever-present glass of iced tea. Despite never having internet access at her home in southern Delaware, my grandmother kept up to date with the latest scientific discoveries as fast as the postman could deliver.

Those magazines comprised some of my earliest reading material, with dog-eared pages marking sections my grandmother eagerly waited to share with me – blue whales in freezing Alaskan waters, lion cubs in African grasslands, an adventurer swallowed up by Yosemite’s grandeur while scaling stomach-sickening walls. Articles in scientific publications were not only a source of entertainment for her, they made her marvel. As I sat cross-legged on the carpet and savored the staple-bound pages, she would recount the particular lines or images that compelled her to crease their corners in preparation for my next visit. Listening to her gush about the worlds she explored from her sofa, I joined in her enthusiasm. It was hard to imagine a person that could resist falling in love with biomedical breakthroughs or newly discovered species from the rainforest after hearing her describe them with such reverence and excitement. At the end of these conversations over magazines and iced tea, I met my grandmother’s sparkling gaze and nodded emphatically as she said, “Isn’t that just incredible?”

Hands-On Experiences

When the magazines did not satiate her curiosity, my grandmother would call and ask me to find the answers to her questions, inspired by her reading. Sometimes I would know something about the topic, but more often I would have to read more to give an answer, like the time she asked me what a Higgs boson, a recently discovered class of subatomic particle, was after hearing it referenced on a television show. No matter what, I would dutifully study the topic of interest and call her back, excited to tell her the facts I had learned, even if I lacked all the answers.

Occasionally, my grandmother’s home library and my internet research failed to placate her inquisitiveness. When this happened, I would rent and deliver books from the public library so she could read further on the topic, though sometimes I was doubtful that even experts would know the answers to the insightful questions she asked.

Though reading transported her to exotic lands and inspired “research projects” on all sorts of unfamiliar topics, my grandmother also loved the nature she observed from her window. The window above her kitchen sink overlooked a bush that housed the local robin’s blue-egged family and the hummingbird feeder that, April through October, was never allowed to be empty. Her favorites were the bluebirds that nested in the backyard birdhouse designated only for them. In the spring, we would chase away the unwanted spider residents so the bluebirds could build their nest. If she didn’t see a pair nesting, my grandmother would make us go check the box and clean it out again, evicting frogs and bees just as they had settled into their would-be home. Even in the winter, a stuffed toy bluebird peered out her kitchen window into the cold, gray skies, as if a lookout for the first signs of spring and the blue-winged visitors that came with it.

Avian Observations and Insights

Backyard Birdwatching

When we visited, my sisters and I would sit barefoot at the bar, trying to catch the rainbows scattered across the counter by the faceted teardrop prism hanging from the window latch, while my grandmother would tell us about the birds she had seen since our last visit. My grandmother did not limit herself to distantly observing the natural world through the glass of journalists’ camera lenses, my computer screen, or her kitchen window. Her love of nature led her to, quite literally, get her hands dirty.

Avian Behavior and Adaptations

While none of her work ever made the scientific journals, my grandmother did plenty of experimenting in one of the few ways accessible to her: gardening. She transformed her house into a well-loved and well-landscaped home with dormant, leafy stubs ordered from nursery catalogs, shaped through much trial and error by her patient hands into a vegetable garden, an orchard with apples, peaches, apricots, and pears, and a flower garden. With the same grit that enabled her to weather her first husband’s departure and divorce, her second husband’s death from cancer, and her son’s death two weeks before his high school graduation, she spent hours relentlessly yanking the weedy invaders that threatened her tidy landscaping. In later years, when emphysema prevented her from working outside, plant cuttings in glass jars balanced precariously on her kitchen windowsill became her primary mode of gardening, while rogue black-eyed susans escaped the edges of her flower garden and dotted her backyard with warm, yellow bursts of petals.

Appreciating Nature’s Wonders

My grandmother passed away when I was in college. At that point, I was a science education major and planned to teach high school biology or chemistry after graduation. Twelve hours away from my hometown, I ditched my teaching assignment in a middle school special education classroom to say goodbye to her over the phone after her recovery from a broken hip took an unexpected turn. I cried the length of that phone call and her funeral a few days after.

Nontraditional Approaches to Science

Practical Problem-Solving

The next summer, I came home from college in early July, determined to spend my time off in my coastal hometown reading and relaxing on the beach, a pastime my Midwest research gig had denied. Cross-legged on my crumpled bedsheets, I opened my laptop and logged into my public library account. Almost immediately, hot tears blurred the screen and spilled onto my keyboard. There, under the holds tab, was a book my grandmother had asked me to reserve over a year earlier, now available to pick up at my earliest convenience. While I don’t remember the title of the book that arrived many months too late for my grandmother to read, the sudden flood of memories that accompanied that moment has not faded.

Holistic Understanding

That moment was a potent reminder of my younger self, the one who, like my grandmother, was obsessed with answering life’s answerless questions. My original choice to become a teacher was inspired by my grandmother’s enthusiasm for sharing knowledge, but it did not quench my desire to experience discovery for myself. While my grandmother could only read about scientists, I realized I could become one of them. I stuck with my education major because I loved working with students, but ultimately my inherited fascination with catching glimpses of undiscovered knowledge compelled me to change my plans and pursue a career in research. Finally, I had found a way to search for the answers that library books had never offered.

Empowering Lifelong Curiosity

Inspiring the Next Generation

While my grandmother served as the initial inspiration for my love of science and eventual choice of career, there are many other reasons why I chose to pursue a career in research. Scientists seek to understand the natural world for a litany of practical and noble reasons: to develop treatments for disease, to invent problem-solving technology, to preserve the natural order of the biosphere, or simply to understand the inner workings of the universe for future scientific endeavors. These reasons motivate scientists to spend hours reading about previous discoveries to inform their own ideas, develop the technical expertise necessary to test their ideas, and communicate their results to others.

Valuing Diverse Perspectives

Scientists pride themselves on thinking critically about their topics of interest, rationally analyzing the evidence and testing their hypotheses from every possible angle. They find satisfaction in the hard work of scientific discovery and in the knowledge that our efforts can make the world a better place. I, too, share these sentiments as primary motivations for my decision to become a scientist. Like many scientists who are trained to think objectively, these impersonal motivations often dominate the professional narrative I tell when people inquire about my career choice. However, I express the real reasons for becoming a scientist, the ones inspired by my grandmother, far less readily.

My grandmother taught me curiosity, open-mindedness, relentless optimism, appreciation of life in all forms, patience for thankless tasks, and grit in the face of disappointment. Each of these qualities are those of a successful scientist, instilled in me by a woman that never donned a pair of gloves or stepped into a laboratory. My grandmother never intentionally set out to teach me these lessons, but they have equipped me to navigate an often-difficult professional journey. These lessons embody who she was and who I am as a result.

So, on behalf of my grandmother, Dorothy Fields, I humbly offer some advice for any scientist, but young ones especially:

- Be curious. Good scientists are great readers. Ask questions and find out the answers. If the answers are not within your reach, ask someone with longer arms.

- Love living things. Care for them, no matter how small.

- Refuse to let circumstances stop you from building a life you love.

- And most importantly: Pursue the things that make you wonder.

My grandmother’s embodied advice is my training and scientific heritage. I wish I could pick up the phone and have one more hour-long conversation with her, detailing our shared obsession with how incredible the world is. But I have these pieces of wisdom and a windowsill full of plants instead, and I am grateful. Even when I doubt myself, these lessons remind me my grandmother inadvertently trained me to be a scientist from a young age.

Instead of being limited by what I do not know, I reach out to the work of other scientists and to peers and mentors who help me interpret the unknown. I refuse to allow the value of life, human or otherwise, to depreciate in my eyes simply because I study it every day. I freely and enthusiastically communicate what I have learned through my teaching and writing so that others may also wonder at the world’s hidden intricacies, which I have been privileged to observe. And I try to learn from, not dwell on, my failures.

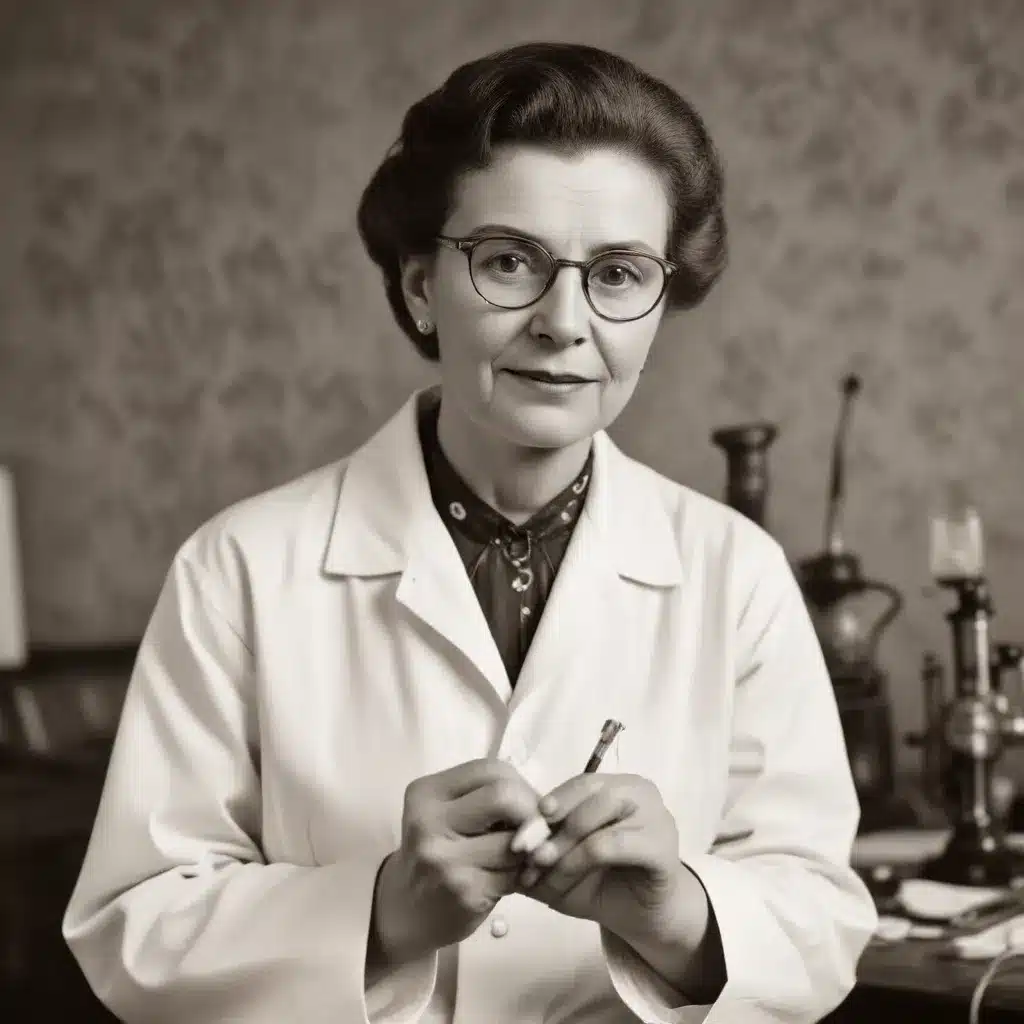

When she passed away, my grandmother had no idea that just a few years later, I would publish original scientific research and go on to study for my Ph.D. Though my active choice to pursue research was recent, my identity as a scientist was formed long ago by a dear woman’s mentorship, a woman that never wore a lab coat. It is in her honor that I wear mine proudly and look beyond the gray skies of inevitable setbacks for the spring-like hope of success and, hopefully—if I am lucky—bluebirds.